Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Circles of Peace

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Oaxaca's New Juvenile Justice System

Friday, October 30, 2009

Peace and Justice in Cuajimoloyas

Cuajimoloyas is a small mountain community in the state of Oaxaca with a population of 900. Its residents are Zapotecs, descendants of the ancient civilization responsible for constructing Monte Alban, the site of the ruins pictured in various photos on this blog. The older residents of the pueblo still speak Zapoteco, although younger generations generally speak Spanish. Until 40 years ago, there was no road leading to Cuajimoloyas. I had the opportunity to visit this community this past weekend, enjoying beautiful hiking trails and interesting conversations with members of the community.

Given that this is an indigenous community, the land is communal, and the pueblo has its own system of governing itself, separate from that of the state of Oaxaca. Each year the pueblo elects a “Municipal Agent,” who is essentially the leader of the community. The community is governed by “usos y costumbres,” a system of customary rules. A sense of community responsibility is intrinsic in these “usos y costumbres,” such as a requirement that each community member dedicate him or herself to community service full-time for one year, every two years. Such community service may include working at the school, in the government, constructing infrastructure such as roads, or working in the community’s Eco-Tourism department.

I was intrigued by the way that the community addresses conflicts, or violations of the law. According to the residents I spoke with, the community has very little conflict or crime. This is due in part because the community is close-knit; with a population of only 900, everyone knows one another. Further, family ties connect many community members. In addition, the community imposes strict consequences for violations, including permanent banishment from the community. A woman told me about an incident that happened a couple of years ago where 2 young men stole a chain saw that they found in the forest. The community had a meeting to determine the appropriate sanction, and the decision was that the young men be banished. Children are raised with the knowledge that failure to abide by the rules of the community will result in certain and swift punishment, including potentially being removed from the community.

Deterrence theory is an important criminological theory that asserts that future crime will be prevented if punishment is certain, swift, and appropriately proportional to the crime. Much of the current criminal justice system of the United States is built upon deterrence theory. I am of the opinion that policies based upon deterrence theory are largely ineffective in the context of the United States. Deterrence theory is based upon the premise that people understand the consequences of their actions before they decide to commit a crime, and that people engage in a rational cost-benefit analysis prior to deciding to commit a crime. This belief drives policies that continue to put harsher and harsher sentences on the books, under the guise that sentences must not be harsh enough if people continue to engage in crime. There are two major problems with this belief: (1) most people who commit crimes are unaware of the sentencing schemes written in the Penal Code; and (2) most people who commit crimes do not engage in this type of rational cost-benefit analysis prior to engaging in criminal behavior.

But deterrence theory does seem quite applicable in the context of Cuajimoloyas. Maybe because the community is involved in determining sanctions, as in the case of the community meeting that determined that banishment was the appropriate response to the theft of the chain saw. The public and inclusive nature of this process means that people are by and large aware of the consequences. In addition, the small population and importance of community norms and customs make deterrence theory more relevant in that people are more likely to be caught for wrongdoing, and consequences are more certain.

Sunday, October 4, 2009

Towards a Culture of Justice

“…la reforma mas importante es la cultural y mental, pues no basta con la creacion de nuevas normas o insticuciones para resolver nuestros problemas…se requiere una cultura juridica alternativa, con una nueva forma de pensar el derecho, mas justa, mas digna, mas humana.”

-M.D. Jose Luis Eloy Morales Brand (2006)

While I’ve been observing within the juvenile prosecutor’s office here, I have been noticing subtle differences in the culture of their organization that stand in contrast to the culture of the prosecuting agencies in Los Angeles. Although it is too early to draw definitive conclusions, there are interesting aspects of the language, values, and orientations of the juvenile prosecutor’s office here that lead me to believe that there is a different kind of culture being developed within this office – one that is rooted in an understanding of adolescent development and the idea that juveniles who commit crimes deserve another chance.

While I’ve been observing within the juvenile prosecutor’s office here, I have been noticing subtle differences in the culture of their organization that stand in contrast to the culture of the prosecuting agencies in Los Angeles. Although it is too early to draw definitive conclusions, there are interesting aspects of the language, values, and orientations of the juvenile prosecutor’s office here that lead me to believe that there is a different kind of culture being developed within this office – one that is rooted in an understanding of adolescent development and the idea that juveniles who commit crimes deserve another chance. Thursday, September 17, 2009

oaxaca's juvenile hall

Oaxaca has one juvenile detention facility for the entire state. This was a shock to me, coming from Los Angeles where there are at least 24 juvenile detention facilities within the County alone. Moreover, there are currently only 26 youth (25 young men and 1 young woman) who are currently incarcerated in Oaxaca’s juvenile hall. I immediately wondered if the reason for so few incarcerated youth was that they are sent to adult facilities. However, I have come to learn that unlike California, Oaxaca does not incarcerate juveniles with adults under any circumstances… There are actually only 26 youth under the age of 18 who are detained in the entire state of Oaxaca.

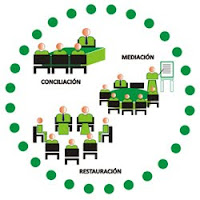

This may be due to the state’s reliance on alternative approaches such as mediation and restorative justice to respond to juvenile crime. There are likely other factors at play here as well, although I do not yet know enough to explore this topic in detail. I suspect that many people who are victims of crime do not report incidents to law enforcement due to a lack of trust. Nonetheless, the numbers are intriguing.

I went on the tour of the juvenile hall this week. I was impressed with the services that are provided to the incarcerated youth, as well as with the culture of the institution. During the tour, I met various employees and observed their interactions with the youth. An overall attitude of caring and respect was apparent.

Each week the staff develop an individualized plan of daily activities for each young person, based upon their specific needs and interests. Vocational classroom activities include carpentry, electrical work, a bakery, and a class where the youth learn a traditional art form using sheet metal. (The metallic rose pictured above was made by one of the youth in this art class). There is also a computer lab, a library, a gym, outdoor recreational facilities, a cafeteria, and educational options ranging from basic literacy to university classes. The center has 4 psychologists on staff who provide psychological services to the youth. In addition, the medical ward includes a doctor and a dentist. The wide variety of vocational classes, as well as the very low staff to youth ratio, are a luxury by Los Angeles standards. This is ironic given that L.A. has more economic resources than does Oaxaca, one of the poorest states in Mexico.

The director of the center informed me that there is a 0% recidivism rate, if we calculate recidivism based on the commission of a new offense. He acknowledges that some youth have returned because they have failed to comply with the equivalent of probation or parole conditions, such as attending school or participating in community service. But over the past two years that the facility has been in operation, no one who has been released has been arrested for committing a new crime. This too is shocking to me given that recidivism rates in California tend to be between 60% and 90%, depending on the facility and how the rate is measured. This is particularly impressive because Oaxaca only incarcerates youth for the most serious offenses, such as homicide, rape, kidnapping, and bank robbery.

How do they have such success? The facility’s director credits using empathy, respect, and setting appropriate boundaries with the youth. He also values offering vocational opportunities that the youth are interested in to provide them with skills, and to keep them busy. I would add that the staff to youth ratio, which is around 1:1 by my calculations, must help quite a bit.

A local prosecutor who has visited a Los Angeles juvenile hall told me today that although the buildings of the Los Angels facility may be nicer, it was missing the element of humanity that is present in Oaxaca’s facility. Although this is ironic in a country where torture is a very real problem entrenched in the criminal justice system, it rings true with what I saw. Sometimes the best practices are simple – treat people with humanity, empathy, and respect. Provide individual attention, psychological support, and educational opportunities.

It may seem simple, but it seems to work.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

letting justice flow

Last week I went to the ruins of ancient Zapotec capital Monte Alban, just outside of Oaxaca City. Perched on top of a mountain, the ruins are spectacular. While wandering around, I came across the remains of a ball court. The plaque that explained the ball game for tourists such as myself indicated that the Zapotecs used this ball game as a means of conflict resolution. When there was a conflict with a neighboring group, for example, a ball game was convened. The idea was that the right person would win. That the will of the gods would be expressed by who won the game. And that this would be respected as the right outcome to the conflict. (As a side note, the plaque also stated that there is no evidence that the Zapotec ball game resulted in death for the loser, as in some other cultures).

This got me thinking… what would it mean to have a process for addressing conflicts through which the will universe – God – a higher power – energy – love – could flow? So that the right outcome just becomes apparent? So that we could transcend our limitations, biases, and all of the other stuff that interferes with our clarity – to arrive at justice…

Last May I participated in a yoga teacher training taught by Erich Shiffman. He emphasized the importance of meditation in order to tap into yourself, and therefore into the universe. So that if you are “tuned in,” you are not left to figure things out on your own – it is more a matter of letting the universe guide you, and flow through you. At the time, I wrestled with how to incorporate this practice into my work in the Los Angeles court system. I felt uncomfortable with the idea of letting things flow, because I felt like I would be allowing injustice if I didn’t intervene. They way I interpreted this concept into my work-day was to regularly pause, connect, and see what would happen next. But it was hard to let things flow in the midst of such a rigidly constructed, adversarial system.

The U.S. criminal justice system is comprised of such elaborate rules, strict procedures, and decision-making power concentrated in the hands of a few people. It is a system whose structure inherently impedes the flow of energy. I wonder how we could create a process that would be more amenable to being influenced by justice, righteousness, love, God, etc…

Since I have been in Oaxaca, I have been learning about the creation of the state’s juvenile justice system – a process that began only 3 years ago. It is fascinating to observe how systems, procedures, and programs are being designed at such an early stage in the creative process. Most cases in the juvenile justice system in Oaxaca seem to be resolved through restorative justice conferences, where the victim, offender, family members, and other affected community members meet to develop mutually agreeable solutions. This seems to be a process that is more amenable to letting justice flow through.

Of course the lawyer in me also gets nervous about the idea of letting go of procedural safeguards…but that’s a whole other post.

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

community based mediation centers

The government of Oaxaca has established 54 mediation centers in cities and small towns throughout the state. Each center houses at least one trained mediator who is available to facilitate mediation sessions at no cost to the participants. These are places where people can go for help and support in resolving all types of conflicts, ranging from family disputes to contractual disagreements. The state is committed to expanding access to mediation services, and the number of mediation centers is growing rapidly. When I was in Oaxaca one year ago, there were 30 centers. In just one year, 24 additional centers have been established!

At a time when Mexico is reforming its criminal justice system to be more like the U.S. system – with oral hearings and trials for the first time in the country’s history – there is a lot that the U.S. can learn from Mexico. Mexico’s court systems are not set up to handle the often time-consuming procedures associated with oral hearings and trials. In the past, court proceedings have occurred purely in written form. As you might guess, once lawyers have the opportunity to speak in court, things tend to take longer! So it is perhaps out of necessity that in the process of designing new procedures to include oral trials, the state of Oaxaca is incorporating alternative ways for people to resolve conflicts.

Aside from the issue of volume, there are other reasons why localized mediation centers are critical in Oaxaca. Firstly, there is the issue of geography. Oaxaca is comprised of two large mountain ranges. Many of the states’ residents live in rural, geographically isolated areas. Streets and highways are costly and therefore scarce in the midst of such enormous mountain ranges. And so for someone who lives in an isolated village to seek help from a court in the nearest city would be extremely difficult. Without a community-based option, many people would have no access to government assistance when they have a conflict (which could otherwise likely be defined as a legal issue.)

In addition to geography, there is the issue of communication. Within the state of Oaxaca, there are many people who do not speak Spanish. In many communities, the primary language is one of 16 different indigenous languages. Due to the language differences, it is even more important that community-based mediators be available to communicate with people at the local level, using the appropriate language and cultural framework in order to successfully mediate conflicts.

At first glance, the issues facing Oaxaca are very different from those in Los Angeles, or in other urban areas of the United States. Upon a deeper inspection, however, there are common threads. In Los Angeles, for example, one court building handles cases from a large geographic radius, making access difficult. Geographic access if even more of an issue given the territorial nature of gangs in the city. Travelling from one community to another means risking being killed for people with gang associations, for example. Perhaps even more importantly, courts and law enforcement offices are not set up to be culturally specific. And although the Los Angeles court system has plenty of interpreters to address the issue of language, true communication often involves a cultural specificity that goes deeper than language. Having community-based mediation centers staffed with mediators familiar with the particular geographic and cultural issues of the community they serve could lead to more meaningful conflict resolution.

A mediator in Oaxaca explained to me that the mediation centers are “an open door” before someone turns to the formal court system. Participation is voluntary, and the parties to the conflict themselves develop a solution. As he was talking, I was thinking about the parents who would bring their children to the juvenile court where I worked as a public defender in Los Angeles. Even though their children had not broken the law, parents would bring them to the court building because they did not know where else to go for help. Similarly, many other parents called the police to respond to family disputes because they did not know where else to go. Imagine if there were accessible community mediation centers that people could turn to for help…